Featured News

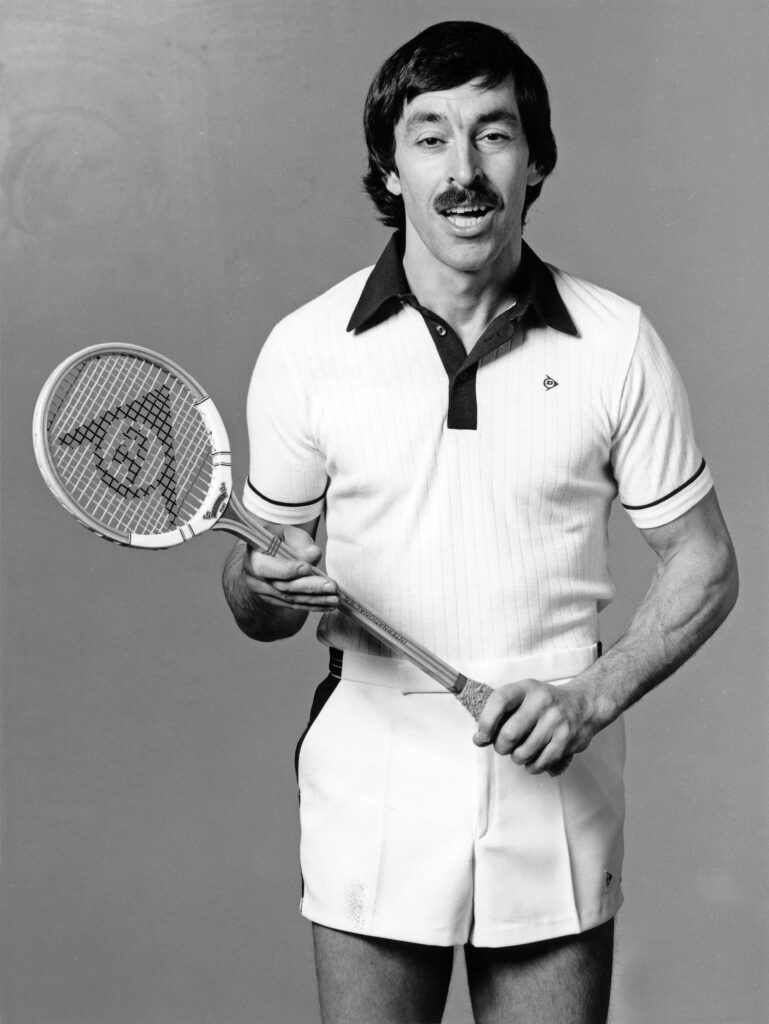

Jonah Barrington – An Icon Of The Game

In the early 1960s Jonah Barrington was a young man without direction, without focus, without aim and in his own words, a man “without talent”.

A university drop-out, who had little to show from his time at Dublin’s Trinity College bar failed exams and an affection for Guinness, his path towards international sporting stardom was as unforeseen as it was exceptional.

Drifting from job to job – even picking up a petty conviction for ‘racing a wheelbarrow down Earl’s Court Road’ – Barrington looked destined to join the long list of could-have-beens before a mid-twenties epiphany transformed the one-time drunkard and began a journey of transformation that would see him not only turn his own life around, but transform the entire sport of squash in the process.

It was a transformation that was set in motion by a chance encounter that very nearly could not have been.

“I went to trials during my first year at Trinity in Dublin and played this guy with a hair net,” said Barrington, who’s is both intensely analytical and humorous in equal measure.

“I think it was a form of cheating because it set me at a considerable disadvantage and he beat me. I was so disgusted and depressed by being beaten by this man in a hair net that I didn’t play for over a year!

“But in my second year one of the squash team approached me and I went down again. The circumstances were different and I was a little bit more mature than the year before so I got involved and it was fantastic. But at the heart of the Leinster League was the Guinness Brewery and we’d go and play them at their home and they had an eight gallon barrel of porter ready on arrival.

“On one occasion I was on last with a guy called Des O’Brien – I don’t know how we played any squash by the time we got on! I thought the whole thing was great, but I didn’t attend classes much – I wasn’t ready to study and didn’t make use of that opportunity. I saw the sport at its most social over there and I did love playing.

“When I disappeared from Trinity I wasn’t involved for quite a period of time after that, but it was always in the back of my mind that I really loved playing the game.

“A short time after Trinity I got an injury in my lower back and whilst I was recovering from that operation I did a lot of soul searching.

“My brother Nick was going through all the requirements of becoming a solicitor at the time. By chance a guy came on holiday to Cornwall where we were living who knew my brother, who was a county level squash player, and he rang to see if he was available to play.

“My brother was away so my mother suggested he play me. I cycled, probably eight miles, to play and afterwards he told me there was a job with the governing body in London and that he’d have a word with the guy who’s running it and that’s how it started – it was just absolute chance.”

That encounter led to another, with Nasrullah Khan, an uncle of Jahangir Khan and then coach at the Edgbaston Priory Club in Birmingham, which proved to be a pivotal turning point for the aimless Barrington. Khan would become a mentor, providing a quiet, methodical tutelage which helped complete the transformation of a dissipated life into an ascetic one.

Shortly before this meeting with Khan, Barrington was beaten for the loss of only two points by Azam Khan, then the world’s best player. But under Nasrullah’s wing Barrington dedicated himself totally, his approach to training and self-improvement becoming the stuff of legend, an by 1967 the Anglo-Irishman had won the British Open for the first time – becoming the first British winner of the iconic event since 1938.

“I met Nasrullah Khan – who became my great friend and mentor,” said Barrington. “I was pretty shy but I approached him and told him that I was recovering from this operation and I really wanted to get fit and see how I could improve my squash. He said ‘cycle to the court on your own for solo practise and hit 100 forehands up the forehand wall and 100 balls up the backhand wall.

“That’s exactly what I did when I got home, every day, and I was getting better.

“My first summer in London I went down to Hampstead Cricket Club every night, and I mean every night. I used to train on the court and there would be no one around because no one played squash in the summer and I used to run round and round the cricket ground while people in the bar would stand there shaking their heads!

“So when it got to April 1965 and everyone stopped, I effectively had a six-month season practising and training on my own. I’d done that cycle for two winters and two summers before I came out in 1966 for the opening match of the season.

“I’d been training non-stop for two years and then I played this guy who was one of the top English players and I beat him for the loss of two points early in the season.

“Three months later I won the British Open – more through fitness than talent,” added Barrington, who downed the previous year’s winner, Abdelfattah Abou Taleb, before defeating 1966 runner-up Aftab Jawaid to clinch the his first title – a feat that would have been incomprehensible just four years previously.

“I knew that once I got the opportunity to find my way in sport that’s what I would do. It started at the British Open and I knew I would work relentlessly to take it the distance.”

It was a victory that heralded a new era for squash. It was the first of six British Open crowns Barrington would collect in the following seven years – a run that laid the foundations for him to transform the sport. His victories, and moreover his career, were a victory for the man of limited means for, as he says himself, there were far more talented players around.

But Barrington had incredible stamina, a court presence and a strong mind. He reckoned he could sometimes create two different scorelines in tough matches – the points tally and the energy count. He would rarely strike the ball low above the tin, aiming instead near or above the cut line, which brought very few errors and very long rallies.

He hit to a length and rarely risked volleys. He tried to make the ball cling. Drops were introduced only gradually and were increased in frequency only during the later stages if his opponent was flagging.

Barrington thus revolutionised ideas about what the body and mind could do, and continued to explore the frontiers of what was possible. He was an early exponent of sports science and sports psychology, and altered how people approached squash, not only professionally, but at all levels of the game.

One of the most commonly used techniques in squash today, ‘Ghosting’, started with Barrington, and tales abound of the man himself performing huge volumes of the exercise in his underpants in the back garden of his Cornwall home – part of a training regime and dedication to fitness that remain legendary to this day.

After winning that first British Open championship, stories emerged that he did some press-ups and then, as the champagne was passed round, discussed his plans for Christmas training runs along his home cliffs of Morwenstow in Cornwall – anything that could gain an edge over his competitors.

Not content with his ascendancy to British Open champion, and the defacto World Champion at the time due to their being no stand-alone World Championship event, Barrington continued to push the boundaries of himself and the sport.

He eschewed the establishment in 1969 and took a plunge into the unknown by becoming the first full-time squash player, accelerating worldwide professionalism in a sport with no world championship, no television and no clear path forward. He embarked on a planet-circling sequence of clinics, tours and exhibitions, helping to lay the foundations, along with Geoff Hunt and Kenny Hiscoe for the creation of the International Squash Players Association in 1974 and a fledgling professional circuit.

“At the time, not just in squash but in all sports, professionals were seen as pariahs, they were outcasts – but I had been watching closely the exploits of Jack Kramer (founder of the ATP professional tennis circuit) and I felt like the attitude of the authorities of the time was to make it so the participants were the last people to get any form of benefit.

“I said very early on, you can’t have a tournament without the players. The players of the most important, not the officials. There were always more officials at an event like the Olympics – but you cannot have an event without the participants. It’s what it’s all about. To the day I die, for me it’s all about those who are participating and taking part – from grassroots all the way through, and we set up ISPA for the benefit of those who participate.

“It was a revolution and I loved being part of it. When we went out on our own, it was marvellous, because we made our own decisions. And very quickly the best amateurs became pro because most players love the idea of playing sport, and maybe extracting a bit of a living out of it – and what a way to make a life. To play a sport professionally, for a considerable part of your life is such a privilege.

“There were all these people from all different walks of life playing squash and it was a wonderful period to be involved in.”

Barrington was a star wherever he went. He was refreshingly forthright, a magnetic raconteur and an incisive commentator. He was unafraid to be controversial. Consequently, he generated publicity like no one before or since. Though he was indeed an extraordinary player, it was as a passionate talker and a spellbinding visionary that he achieved more and brought the sport of squash into mainstream consciousness through the 1970s – a time when the sport enjoyed unprecendented growth on a global scale.

He remained amongst the world’s top 10 until he was 40 and continued to be a leading light for the sport wherever he went. After retiring from competition, his involvement in the game continued, from lending his voice to television broadcast around the world, leading coaching roadshows up and down the British Isles, coaching the England National team, creating a squash academy at Millfield School, coaching and mentoring some of the game’s greatest recent exponents including the likes of Mohamed ElShorbagy to name but a few.

Today, 50 years on from the creation of the ISPA – now the PSA – Barrington’s name still carries an aura and a sense of awe. He is not just an historical figure, he is still very much an influencer on the sport and the great pioneer is, and will always remain, a true icon of the game who’s presence will forever be felt.